“How the fuck are you still alive?” Eli asked bootlegger and notoriously pragmatic weasel Micky Doyle in the season three premiere of Boardwalk Empire. Two years later, the greater mystery is how their show, a once-surefire hit for HBO, is not.

In just two months, Boardwalk Empire will shutter its doors, its final eight-episode season passing through the airwaves as silently as the ghosts its cast so elegantly portrays. Four years ago, when the show was just premiering, such an innocuous ending seemed as unlikely as the age discrepancy between Jimmy Darmody and his mother. HBO had picked up the prohibition-era drama from Terrance Winter, one of the key cogs of The Sopranos’ writing staff. They surrounded him with can’t-miss weapons, from pilot director Martin Scorsese to star Steve Buscemi to other established Hollywood talent, including Trainspotting’s Kelly McDonald, Revolutionary Road’s Michael Shannon, and Dawson’s Creek alum Michael Pitt. To cap it off, the premium cable network spent upwards of five-million dollars to construct its 300-foot, central boardwalk set, then the most expensive outdoor set ever built for a television show. It was so grandiose that the A.V. Club’s Noel Murray described Boardwalk as such in his review of its pilot episode:

“In gambling parlance, HBO’s new series Boardwalk Empire is about as close as TV gets to a sure thing… I’ve read some critics grumbling that the show is ‘exactly what you’d expect,’ by which they mean that, yeah, sure, it’s entertaining and sophisticated and snazzy, but it’s not especially challenging. To some extent, I get where they’re coming from. Some critics prefer to root for scrappy underdogs, and touting Boardwalk Empire is more like cheering on the New York Yankees.”

Murray goes on to say, “But hell, I’m not afraid to say it: Go Yankees!” A key to enjoying Boardwalk from its start (okay, to enjoying anything, really) is to get on its wavelength as quickly as possible, ignoring unfounded perceptions of what it “should” be. At its birth, some said that it wasn’t violent enough, given its source material. Such claims seem ludicrous, given how Boardwalk features some of those most brutal executions on television this side of a Mountain vs. Viper melee. It wasn’t a prying character study like Mad Men, though elements of that show are certainly present (some more successfully incorporated than others.) It wasn’t a slow-burning action drama like Breaking Bad, though there were elements of that as well, specifically in its attachment to vivid action cinematography. It had more in common with classic gangster films from the likes of Scorsese and his peers, though its long-form storytelling meant a naturally slower pace than crime-movie aficionados were used to. It seemed that whatever people wanted Boardwalk Empire to be, it was not. Yet it was never anything more than what it presented itself as from the start: a straightforward, novel-like crime tale with fascinating – if not immensely complex – characters, set in an ever-expanding universe both similar to and very unlike our own.

In actuality, for a show set nearly 100 years in the past, Boardwalk Empire was just a tick ahead of its time. A typical Boardwalk scene consists of two characters having a conversation with one another, which would quietly adhere into a larger narrative, both in terms of the episode and the season. As early as season one, Boardwalk displayed a natural gift for wrapping up each of its sprawling storylines into a satisfying, cohesive whole. Seemingly disparate threads, such as an alliance in season three that brings forth a stunning firefight in its season finale, could never be discounted. Bonus points were awarded to viewers who remembered the most mundane details. The problem for many viewers was that these dialogue-heavy scenes would often overshadow the climactic, bullet-riddled, historically-soaked massacres they built towards.

Then, just four months later, Game of Thrones debuted on HBO, and was able to build its reputation around the latter kind of action scenes, while still largely operating under Boardwalk’s “two people talking” over-arching scene structure. While Boardwalk’s ratings would tellingly peak with its first season finale at 3.29 million viewers, Thrones only rose from its modest first season numbers, seemingly stealing away all available buzz from Boardwalk to get to the absurd 7 million viewer ratings it now averages (before piracy numbers). It could simply be a matter of America being more interested in dragon queens and Bieber kings than booze raids and pork pie hats at the moment, but such a huge ratings discrepancy is still odd for two shows on the same network that move at such a similar pace within such a similar structure. (This isn’t to say other shows didn’t share variations of this structure, HBO’s own The Wire included, but no shows had ever been quite so written like a novel for television, or shot with a level of professionalism that captured those novelistic qualities.)

To be sure, Boardwalk Empire was never a perfect show. Despite its outstanding ensemble, it focused too predominately on protagonist Nucky Thompson, sometimes trying to pry more out of the character than was actually there. Buscemi is great in the role, but unlike, say, James Gandolfini or Bryan Cranston, it’s a character that you can admittedly see a number of other actors handling. In fact, in its best seasons, two and four, Boardwalk essentially turned two of its strongest characters – Michael Pitt’s Jimmy Darmody and Michael K. William’s Chalky White – into co-leads. And for a show that never shied away from ambition, Boardwalk could occasionally stumble when it tried to search for too much meaning. In its first season, especially, its overt symbolism and imagery could land with the subtlety of Richard Harrow inquiring as to what love feels like. Take the seventh episode of the series, “Home,” in which Nucky’s abusive father is forced to move out of Nucky’s childhood home. Nucky offers it to his associate, the aptly-named Damien, before reflecting on the put-downs (and beat-downs) he endured from his father all his life, promptly burning the house to the ground instead. He gives Damien a stack of cash and tells him, “Go find yourself a better place to live.” It’s not exactly nuanced storytelling, and unfortunately wasn’t the only such instance.

Yet that was also the episode that featured the debut of fan-favorite assassin Richard Harrow, a man with a tin face but a heart of gold. That was the ultimate gift of Boardwalk: even when some storylines weren’t clicking, there was still more than enough legitimate entertainment in any given episode to make each installment well worth your time. The latter half of season two features a completely devastating and largely unnecessary polio sub-plot, one that’s more than balanced out by Richard longing for a family and a normal life. For every scene in season three or four that suggested Gillian was overstaying her narrative welcome in lieu of her son Jimmy’s death, there was a scene of Michael Shannon’s insanely no-nonsense prohibition officer-turned-mob lackey Nelson Van Alden (potentially my favorite television character of the last decade, if only for Shannon’s most unhinged, Shannon-esque performance ever) destroying colleagues with a scalding iron. And though Boardwalk’s writing staff more or less adhered to historical events as they actually transpired, such as George Remus’s arrest or Arnold Rothstein’s death, they also took every creative liberty possible, such as having George Remus refer to himself in the third person, or having the always-articulate Rothstein rehearse his general cadence before taking a business call. Make no mistake: Boardwalk was never a comedy. But it also never took itself too seriously, which crucially kept it closer to a self-aware romp than a self-indulgent slog.

It didn’t hurt that the whole thing was a freaking marvel to look at. Though Breaking Bad had come along first and demonstrated what television cinematography was capable of, Boardwalk in itself could teach an entire film class, let alone a television class. The Boardwalk set eventually proved too expensive to use in later seasons, but its level of detail and color in the early seasons remains a visual feat. Great directors like Tim Van Patten were able to keep the show consistently well-lit, despite the majority of it taking place at night. And each shot is staged so precisely and with such a level of care that its honestly hard to tell a typical episode apart from Scorsese’s pilot.

Then there’s the performances. I’ve touched on Buscemi and Shannon, but the entire, sprawling ensemble brings something to the table. Only Stephen Graham’s Al Capone could take a scene that began with Capone slapping around his young son and turn it into maybe the most affecting scene in the show. Michael Stuhlbarg turns World Series-rigging Arnold Rothstein into an omnipresent, well-mannered sociopath. Gretchen Mol’s Gillian Darmody is perhaps the most controversial character on the show, but her somewhat-wooden acting proved to be perfectly in line with her character’s fucked-up psychosis. Jack Huston immediately goes into the “how were they never nominated for an Emmy?” Hall of Fame with his brilliantly nuanced performance as Richard Harrow. Jeffrey Wright provided a fascinating foil to Chalky in the show’s fourth season as Dr. Narcisse, a savvy and manipulative businessman who could hold his own in a world already stuffed with them. Bobby Cannavale chewed the scenery gloriously for twelve straight episodes en route to an Emmy of his own. (Hell yeah I’m a Gyp Rosetti defender). Paul Sparks re-invented the weasel laugh. Kelly McDonald could flip her undeniable Irish accent from sexy to no-nonsense in a heart beat. And so on so forth.

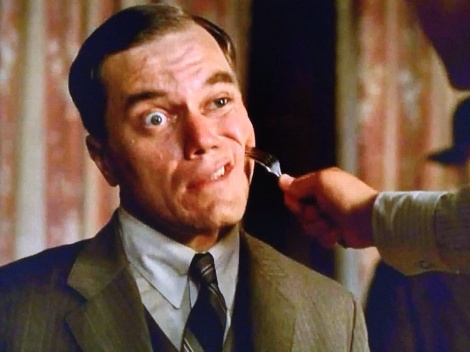

It’s telling that season two – which featured an all-out war between Nucky and Jimmy – was its best, as much of its proposed script was apparently tampered with by off-camera issues. It’s widely speculated that Jimmy’s death in the season finale was not something the writers planned, but was rather necessitated by how difficult Michael Pitt was to work with. (Just Bing ‘Michael Pitt Boardwalk Headache’ and you’ll get the full story. Yes, that’s right. I Bing now.) And Jimmy’s father, the Commodore, was supposed to be a much larger presence in the story, but Dabney Coleman was largely sidelined after just three episodes due health issues. Despite these obstacles, Boardwalk was able to craft an elaborate, tension-filled season of television. Especially in the first half of the season, you can practically see the Sword of Damocles hanging over Nucky Thompson’s head, recalling the great later seasons of The Shield or that one good season of Dexter.

So, fittingly, the show is now coming to its own abbreviated ending with more behind-the-scenes drama. Winter has proclaimed that ending the show now was a creative choice, as the writers had discovered that Nucky’s story was wrapping up faster than they had intended (there it is again, the misplaced assumption that this show’s primarily about Nucky). But it still feels like Winter is playing nice with HBO because he’s trying to get a new show launched with them. For their part, HBO seems like it’s trying to gently push the show out the back door in lieu of its declining ratings and sudden award show nomination shutouts. Eight episodes – essentially the end of Act 2 in a standard Boardwalk season – just feels strange for a show that moved so deliberately. And with the promise of a seven year time jump – one that will skip over a number of key events the show was seemingly gearing towards – as well as flashbacks to the childhood lives of Nucky and Eli, it seemed like the abridged final season could be a disaster. To the show’s credit, last Sunday’s premiere was most assuredly not that, and the flashbacks were even somewhat admirable, trying to grasp a bit of poetry out of whatever final story they’re trying to tell. Plus, next week’s previews promise a Van Alden / Eli team-up, something it impossibly feels like I’ve been waiting for my entire damn life.

As a fan, though, it’s hard to call it anything but a shame that Boardwalk couldn’t carry on through its timeline naturally for two or three more seasons. It may have started out as the Yankees, but remember that the Yankees were in the process of defending a World Series in 2010. In 2014, they’re struggling to make the playoffs once again, and there’s no Arnold Rothstein around to rig it for them nowadays. Instead, former stars like Mariano Rivera and Derek Jeter are stepping away from the spotlight just like Richard Harrow and Enoch Thompson. In a more perfect world, it could have joined Game of Thrones and True Detective (another HBO drama with a similar, conversational structure) to form a trio that would perhaps not rival HBO’s Sopranos-Deadwood-The Wire “Golden Era,” but provide an immensely satisfying silver age. Yet that feels like a disservice for a show as constantly entertaining as Boardwalk was over a stretch of four years. Given that the ultimate downfall for so many of Boardwalk’s assorted gangsters was their unwavering desire to want more than they already had, perhaps it’s best this way: accepting what Terrance Winter and company have given us and walking away, before everything can fall apart.

Just a brilliant summation that perfectly codifies my feelings about this amazing show which I miss so much.

Thank you! I really do think this show was criminally under-appreciated.